A new era is dawning in the realm of medicine and the tools fueling this revolution are right at our fingertips. Thanks to the creative use of smartphone sensors, researchers are finding new ways to diagnose conditions using little more than the devices in your pockets.

Data from our pockets

No two people are the same, and no two bodies are the same — but being able to offer individualized healthcare would require an immense amount of data. In modern times, however, we do have access to this data. Smartphones, smartwatches, and other wearable devices are more than just communication tools or fashion accessories, they are data powerhouses. These ubiquitous devices are gathering a trove of information about our daily lives, from the number of steps we take to our sleeping patterns, heart rate, and more. Researchers increasingly believe that we can use this data to offer better healthcare to people.

Shwetak Patel is one of the people at the forefront of this revolution. Patel was awarded the 2018 ACM Prize in Computing for his contributions to low-cost sustainability and health sensors. He is currently working at the University of Washington, focusing specifically on low-cost and easy-to-deploy sensing systems.

“My research looks at how to use mobile devices, the sensors on mobile devices for screening and diagnosis, but also using AI to help administer all kinds of health and wellness use cases on phones and mobile devices,” Patel told ZME Science at the 2023 Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting.

“My research looks at how to use mobile devices, the sensors on mobile devices for screening and diagnosis, but also using AI to help administer all kinds of health and wellness use cases on phones and mobile devices,” Patel told ZME Science at the 2023 Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting.

Commercial smartwatches and smartphones can already offer an impressive array of data, but Patel wants to push the boundaries even further. A smartphone already has a speaker, microphone, cameras, accelerometer, magnetometer, gyroscope, and a bunch of other sensors or tools that can be used for diagnosis and screening.

“Phones are already very capable in terms of computational power and sensing. But we’re wondering, ‘what if you augment it a little bit, what can you do?'” says Patel.

Previously, Patel looked at how camera apps could be used to monitor blood oxygen and how to differentiate between different types of coughs. Now, he’s looking at a big problem.

“If I want to screen the entire planet for diabetes, how can I do it?” he asked the audience in a lecture. His approach is to use the phone as a glucometer.

Sugar and smartphones

Glucometers (devices that measure people’s blood sugar) work in a pretty straightforward fashion. You prick your finger and get a drop of blood and you put the drop on a test strip. Then, you insert the strip into a glucometer which then turns your blood sugar level into electric signals and measures it.

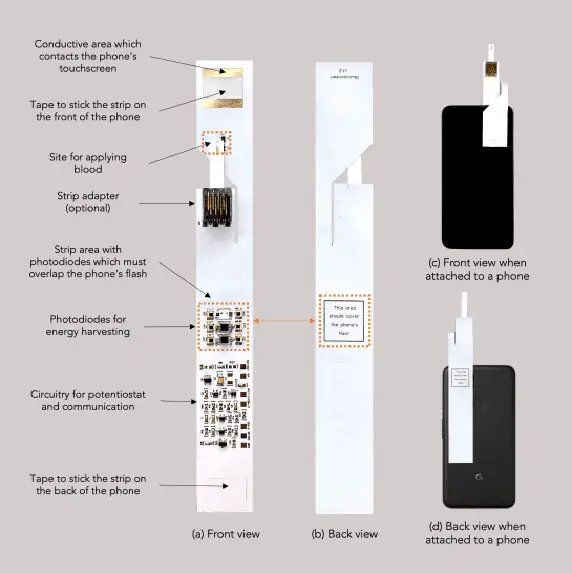

The solution works by placing the customized test strip on the smartphone camera and then specialized software offers the results. Image credits: ACM / Waghmare et al (2023).

Basic glucometers are fairly affordable; you can probably get a decent one for $20. You also have to buy test strips that cost under $1 but are usually sold in bulk. But you’re not going to screen the entire planet by getting everyone glucometers. Even for people who are at risk and should undergo testing every couple of years, this is not a purchase that they are likely to make.

But with smartphones, you have a shot at getting an entire population tested.

Around 86% of the world’s population owns smartphones. So the challenge is to transform phones into something that can measure blood sugar levels, Patel says. If you want to screen an entire population, the researcher explains, you just have to ship the strip to everyone and then you have phones as the measuring instrument.

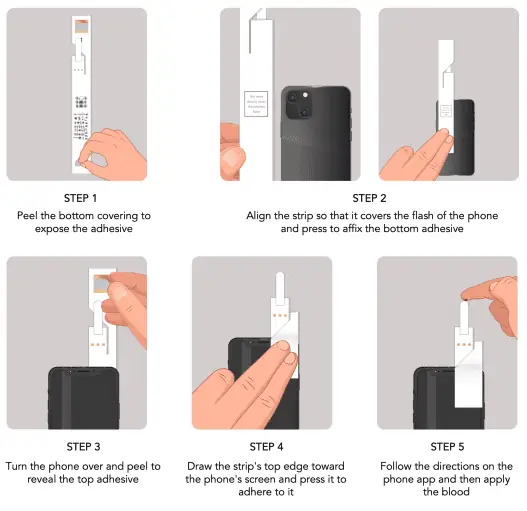

Patel usually works with smartphone sensors as they are. But in this case, a bit of augmentation is necessary. The process is straightforward, the researchers explain.

Patel and his colleagues wrote a paper in which they detail the solution, which they call GlucoScreen. In order for it to work, they had to tweak the test strips a bit to make them smartphone-readable. In the paper, they describe GlucoScreen thusly:

The researchers estimate that if you do things efficiently, you can get one strip with two tests for $2.8 (so $1.4 per strip), and it behaves comparably to commercial glucometers. But even if it was a bit worse, that’s probably not that bad.

Lots of imperfect, small measurements produce better results

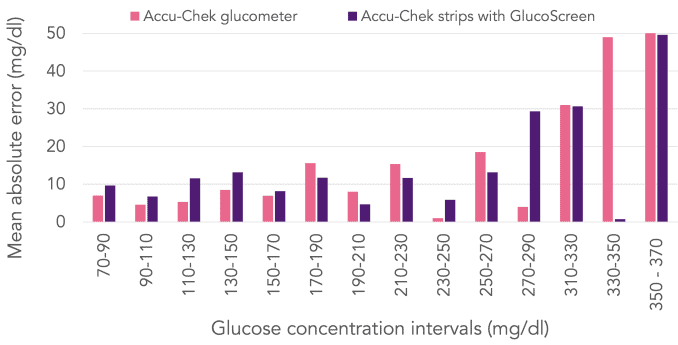

Results derived from the cross-validation analysis of clinical study data. Comparison from the research.

The error in glucose concentration prediction with GlucoScreen is comparable to that of commodity glucometers, the researchers say. But Patel argues that even if the analysis isn’t perfect, it’s better to have multiple imperfect measurements rather than one single perfect measurement. Your biophysical parameters can change significantly from day to day or from hour to hour. Even just being in a clinic can trigger a meaningful shift. So instead, having a continuous flux of information is more valuable, Patel mentions.

“So one of the things that we found is that, for a lot of our sensing work, you actually don’t need to be perfectly accurate compared to a clinical diagnostic. If you think about it, if you had a sample of somebody’s vitals every single day, that’s actually more powerful than one very accurate reading once a year. “

The researcher adds that in many instances, following the trends of one’s readings is as important as the values themselves.

“Having multiple measurements might actually be more valuable because that can tell you if something’s going wrong, or if somebody is getting ill well before you would ever have a clinical visit. So accuracy is an important thing but we should also look at it in the context of what it is being used for.”

The future of screening

Around 600 million people have diabetes now, and the number is estimated to grow to 1.3 billion by 2050. Plenty more have prediabetes.

Many other conditions could potentially benefit from similar smartphone-based diagnostics. Hypertension, heart diseases, asthma, and even mental health conditions could see innovative screening methods using this versatile technology. The use of smartphones for health screening is not limited to wealthy countries, either. With smartphone penetration increasing even in low- and middle-income nations, the scope for this technology to bring healthcare to underserved populations is immense.

In Patel’s vision, the future is a world where health screening is democratized and decentralized. Rather than relying solely on healthcare facilities and specialized equipment, people could leverage the devices they already own to monitor their health on an ongoing basis. This could lead to earlier detection of health problems, more personalized care, and, ultimately, improved health outcomes globally.

But this future is not without challenges. There are concerns about the accuracy and reliability of smartphone-based diagnostics, and issues around data privacy must be addressed. Regulation and standardization of these new technologies are essential to ensure they meet medical standards and that users can trust them.

Patel, who also collaborates with Google, says some of his work also addresses this and he’s a firm advocate of empowering users with their own data.

Re-posted by Nguyen Le Quynh Giang on September 15, 2023| VISHC News